THE

VOICE OF THE YESIDI

Copyright © Dave

Mockaitis. All Rights Reserved

In her 2005 memoir, “Love My Rifle More Than You,” linguist

and former intelligence specialist Kayla Williams described her military

experiences near the Northern Iraq-Syria border. The work is unique

because it provides Western civilization an accessible yet brief glimpse

of the Kurdish-speaking group, the Yezidi. The Yezidi, a Kurdish religion

with ancient Indo-European roots, is thought to have developed out

of the prehistoric Mitrhaic and Mesopotamian religious traditions (Yazidi).

Williams was able to interact with the Yezidi in part because the Yezidi

are grateful for the US occupation of Iraq that protects them from

persecution by local Muslims that considered them to be devil-worshippers.

Though she did not study the group extensively, she understood their

religion as very ancient and concerned with angels. Most significant

is Williams encounter with a Yezidi shrine on a mountaintop which she

describes as “a small rock building with objects dangling from

the ceiling” with alcoves for the placement of offerings (Yazidi).

These dangling objects are a contemporary manifestation of an

ancient practice of working with astrological phenomena in a physical,

embodied

way.

The

iconography of the Yezidi appears to be disproportionately populated

by jars. In the Yezidi version of the myth of Adam and Eve, both

fill jars with their seed and wait to see what grows. When Eve yields

only insects and Adam a beautiful baby boy, humanity is born and

considered to be solely a result of Adam’s divinity. The central

figure of Yezidi faith is Melek Taus, a benevolent angel depicted

as a peacock that fell from grace but redeemed himself. In repenting,

the angel wept for 7,000 years filling seven jars which quenched

the fires of hell (Yezidi, Melek Taus). The image of a jar or crucible,

is pivotal to the work of the Renaissance alchemist. Containing experiments

and energies, these crucibles speak to the notion of embodying and

containing divine, powerful forces. The fact that Melek Talus wept

seven jars is also significant, as the Yezidi believe that God entrusted

the care of the world to a heptad of seven holy beings often conceptualized

as angels (Yezidi). Closer study of Yezidi texts and scriptures may

show that these seven holy beings were in fact created through the

peacock angel’s tears, that through containing such intense

remorse and sadness, compassionate angels were forged.

The

iconography of the Yezidi appears to be disproportionately populated

by jars. In the Yezidi version of the myth of Adam and Eve, both

fill jars with their seed and wait to see what grows. When Eve yields

only insects and Adam a beautiful baby boy, humanity is born and

considered to be solely a result of Adam’s divinity. The central

figure of Yezidi faith is Melek Taus, a benevolent angel depicted

as a peacock that fell from grace but redeemed himself. In repenting,

the angel wept for 7,000 years filling seven jars which quenched

the fires of hell (Yezidi, Melek Taus). The image of a jar or crucible,

is pivotal to the work of the Renaissance alchemist. Containing experiments

and energies, these crucibles speak to the notion of embodying and

containing divine, powerful forces. The fact that Melek Talus wept

seven jars is also significant, as the Yezidi believe that God entrusted

the care of the world to a heptad of seven holy beings often conceptualized

as angels (Yezidi). Closer study of Yezidi texts and scriptures may

show that these seven holy beings were in fact created through the

peacock angel’s tears, that through containing such intense

remorse and sadness, compassionate angels were forged.

This idea of containing and transforming energies in crucibles is

significant in the fact that the voice of the Yezidi speaks strongest

in the texts consulted by Renaissance magicians. The Picatrix has had

a profound influence on Occultists since it was first collated in 10th

century Arabia. Primarily a handbook on talismanic magic, the book

also serves as a compilation of Arabic texts on hermeticism, astrology,

alchemy and magic in the 9th and 10th centuries (Picatrix). Used by

Marsilio Ficino, William Lily, and a host of other astrologers and

magicians past and present, the four volume work describes a way of

working with planetary energies that is grounded in both astrological

practice and material reality. Working with the Picatrix entails harnessing

the energy of an astrological body into a material object so that the

energy can be introduced to situations the mage seeks to change (Warnock,

Picatrix). Instead of deriving information and predictions from the

movement of the stars, many Renaissance astrologers and magicians were

deriving the actual energy of of the planets and fixed stars, themselves.

This materialist approach is grounded in a tradition that can feasibly

trace its roots to the observational astrologers of prehistoric Mesopotamia.

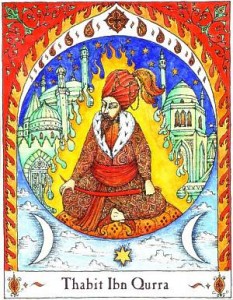

Thabit

Ibn Qurra translated and collected texts in Baghdad in the late

9th century. His work, De Imaginibus (“On Images”), was a key

source for the Picatrix, as it displayed a sophisticated form of astrological

magic derived from the works of the Harranian Sabians. Fluent in Arabic,

Greek, and Syriac, Ibn Qurra’s services were invaluable at the

House of Wisdom (Bayt al Hakim), a facility in Baghdad that amassed

and translated current and historical texts (Warnock “Ibn Qurra”,

Thabit Ibn Qurra). Ptolemy and Euclid are just two scholars that

were translated by Ibn Qurra. It was his knowledge of Harranian Sabian

esotericism,

though, that may be his most unique contribution to the field.

Born in 836 CE in Harran, Mesopotamia (modern day Turkey), Ibn Qurra

grew

up with the Sabians of Harran, a sect of star-worshippers that

received protection under Muslim rule. Like their cultural descendant,

the Yezidi,

the Harranian Sabians also held a belief system with an emphasis

on the intervention of angels (Sabians). In the angelology of the Harranian

Sabians, the link between these angels and the seven visible

planetary

bodies is clear. The angels are the planets and they are directly

accessible through the appropriate astrological invocation (Sabians).

Renaissance

scholar Christopher Warnock notes that in fact the Harranian

Sabians are the pagan followers of Hermes Trismegistus.

Thabit

Ibn Qurra translated and collected texts in Baghdad in the late

9th century. His work, De Imaginibus (“On Images”), was a key

source for the Picatrix, as it displayed a sophisticated form of astrological

magic derived from the works of the Harranian Sabians. Fluent in Arabic,

Greek, and Syriac, Ibn Qurra’s services were invaluable at the

House of Wisdom (Bayt al Hakim), a facility in Baghdad that amassed

and translated current and historical texts (Warnock “Ibn Qurra”,

Thabit Ibn Qurra). Ptolemy and Euclid are just two scholars that

were translated by Ibn Qurra. It was his knowledge of Harranian Sabian

esotericism,

though, that may be his most unique contribution to the field.

Born in 836 CE in Harran, Mesopotamia (modern day Turkey), Ibn Qurra

grew

up with the Sabians of Harran, a sect of star-worshippers that

received protection under Muslim rule. Like their cultural descendant,

the Yezidi,

the Harranian Sabians also held a belief system with an emphasis

on the intervention of angels (Sabians). In the angelology of the Harranian

Sabians, the link between these angels and the seven visible

planetary

bodies is clear. The angels are the planets and they are directly

accessible through the appropriate astrological invocation (Sabians).

Renaissance

scholar Christopher Warnock notes that in fact the Harranian

Sabians are the pagan followers of Hermes Trismegistus.

The works of Hermes Trismegistus

occupy an interesting convergence of astrological and magical thought,

as he figures as a sort of mythic

ancestor to both traditions. Worshipped by both Egyptians and

Greeks as an embodiment of Thoth or Mercury, respectively, Hermes

Tristmegistus

is a bit of a mystery. Many Hellenistic astrologers used his

name to imbue their works with authenticity and authority. Tens of

thousands

of texts are attributed to him, which has led scholars to simply

categorize these texts as Hermetica, referring to documents that

contain secret

wisdom, spells and induction procedures from the 2nd and 3rd

centuries CE (Hermes Trismegistus, Hermetica). The emerald tablets

of Hermes

Trismegistus, considered to be one of the oldest Hermetic texts,

contains the phrase “as above, so below,” a dictum used

by many astrologers to explain the correspondence between movements

of the

heavenly bodies and events transpiring on Earth (Emerald Tablet).

The phrase is instructive for magicians as well, as it eloquently

summarizes

the the theory behind the Hermetic practice of sympathetic magic.

The works of Hermes Trismegistus

occupy an interesting convergence of astrological and magical thought,

as he figures as a sort of mythic

ancestor to both traditions. Worshipped by both Egyptians and

Greeks as an embodiment of Thoth or Mercury, respectively, Hermes

Tristmegistus

is a bit of a mystery. Many Hellenistic astrologers used his

name to imbue their works with authenticity and authority. Tens of

thousands

of texts are attributed to him, which has led scholars to simply

categorize these texts as Hermetica, referring to documents that

contain secret

wisdom, spells and induction procedures from the 2nd and 3rd

centuries CE (Hermes Trismegistus, Hermetica). The emerald tablets

of Hermes

Trismegistus, considered to be one of the oldest Hermetic texts,

contains the phrase “as above, so below,” a dictum used

by many astrologers to explain the correspondence between movements

of the

heavenly bodies and events transpiring on Earth (Emerald Tablet).

The phrase is instructive for magicians as well, as it eloquently

summarizes

the the theory behind the Hermetic practice of sympathetic magic.

Hermeticists believe that

everything proceeds from a source referred to as “the one” in a logical, hierarchical manner. The

one source of all has a consciousness which occupies the second tier

of this system. The consciousness is often referred to as the demiurge,

the logos, or thought of the one. It is the repository of ideal forms

and Platonic ideals which generate the next level, the anima mundi

or soul of the cosmos. Warnock describes the anima mundi as “thoughts

in the mind of the divine” (Warnock “Hermetic Gnosis”).

Where the one source is a pure state of being and the demiurge is the

capacity for thought or the possibilities which can be thought, the

anima mundi is the actual content of this universal consciousness.

The celestial world is comprised of the cosmos which occupies the next

level and represents the mechanism which “the one” utilizes

to embody the ideas arising from the anima mundi. Finally, at the bottom

of the ladder is the material form and material world. Here is where

the corporeal experience of humanity lies, the result of a divine source

manifest through the movement of celestial bodies. This theory blends

seamlessly with early Greek Stoic and Platonic thought. The dictum “as

above, so below” describes the connection between the core level

of reality experienced by humans and the movements of the heavenly

bodies. In contemporary astrology, it is generally thought that planetary

phenomena cause or are reflected in events on Earth. However, the magical

tradition takes this concept one step further by harnessing or cocreating

with the planetary phenomena. Many hermeticists feel that these acts

even comprise a spiritual practice because by working with the planets,

they come closer to “the one” (Warnock “Hermetic

Gnosis).

The Picatrix is significant

astrologically because it provides a wealth of examples of astrologers

using Hermetic principles to contain planetary

energies to create effects in the material realm. Furthermore,

it solidifies the connection between the Harranian Sabians and the

Yezidis of Kurdistan.

Four chapters comprise the first book of the Picatrix. The first

three books focus on the astrological and philosophical background

behind

magic, while the fourth which offers direct and explicit instructions “is

about the magic of the Kurds, Nabataeans, and Abyssinians” (Warnock “Picatrix”).

In a work that’s comprised of more than 200 previous magical,

astrological and philosophical texts, it’s significant that these

cultures are specifically mentioned by name (Warnock “Picatrix”).

These cultural groups are also likely the source for the doctrine of

planetary hours, which informs the ways in which an astrologer elects

a chart. The Chaldean order of planets, the basis for working with

planetary hours, was likely developed in Babylon or Mesopotamia many

years before Common Era (Warnock “Planetary Hours,” Chaldea).

It was therefore copresent with the Kurds, Nabataeans and Abyssinians

and surely comprised a part of their magical/astrological practice.

It’s clear that the Picatrix helps chart the metaphysical lineage

of astrology. Already in Ptolemy’s times, there exists a fully

formed mathematical system of divination, but what Ptolemy’s

system lacks is a clear explanation of why the planets represent

that which they symbolize. The magical/astrological tradition represents

a kind of folk-science of trial and error. Approaching the planets

as forces which can be worked with and embodied, the mage is

in a position

of active engagement with the solar system, rather than merely

reporting on what is likely to transpire. The Yezidi are proof, then,

that alternative

astrologies are alive if not doing terribly well. As the descendants

of a group with a materialist approach to the cosmos, the Yezidi

may be the closest living link to the prehistoric Mesopotamian roots

of

astrology.

References